A Partnership in Art With Jeremy Sorese and Holden Brown

- 23 May 2019

- ByMitchell Kuga

Throughout his twenties, cartoonist Jeremy Sorese dated a handful of artists.

“And it was always a mess,” he says, sitting in his sun-lit bedroom in the Ditmas Park neighborhood of Brooklyn. He recalls sitting next to a guy he was dating and watching him swipe past an illustration he had just posted on Instagram. Or that time a different guy said it made sense that Jeremy liked a chintzy ornament his mother had made because he was a “commercial illustrator,” not a capital “A” artist. “And I agreed with him!” he says. “It's literally just words, but it shapes so much of how you see yourself and your work.”

As a result, Jeremy avoided thinking of himself an an artist. Despite teaching courses on drawing and character design at Maryland Institute College of Art. Despite illustrating for publications like The New York Times, The Village Voice, and Businessweek. And despite publishing a 420-page graphic novel that was nominated for a 2015 Lambda Literary Award, “I just shrank myself down more and more to accommodate men,” he says.

He thought the answer was to avoid dating artists. But in the fall of 2017 he met Holden Brown. At the urging of a mutual friend they followed each other on Instagram, where they liked each others selfies and eventually started messaging, falling into a rhythmic banter. “Talking about What's Up, Doc? was a big deal to me,” says Jeremy, referring to the 1972 romantic comedy that pays tribute to the Bugs Bunny franchise. “I was not used to men having articulate things to say about Barbra Streisand movies.”

Original photography of Holden (left) and Jeremy by Mitchell Kuga.

After three weeks of exchanging Instagram messages, they met for lunch at Xi'an Famous Foods. Though Holden ordered the messiest thing on the menu (“I felt like I was making a fool out of myself,” he says), lunch unexpectedly turned into a marathon: a 50-block walk along Central Park, a kiss on the street before buying coffees (“I didn’t want our first kiss to be with coffee breath,” Jeremy says), and a stroll through The Metropolitan Museum of Art (“It was very When Harry Met Sally,” Holden says) before a dinner of Tibetan dumplings in Ditmas Park.

A mixed media artist working primarily in installation and video, Holden was an echo of previous men Jeremy had dated - a real artist. He possessed an impressive and at times intimidating grasp of the art world, sharpened through regular visits to galleries and museums throughout the city. Through his discerning eye, he had developed a bit of an art crush. “I think I fell in love with Jeremy's art before I fell in love with Jeremy,” the 28-year-old says. “He's really interested in people and really loves people. How he expresses that through color and texture and composition really moved me.”

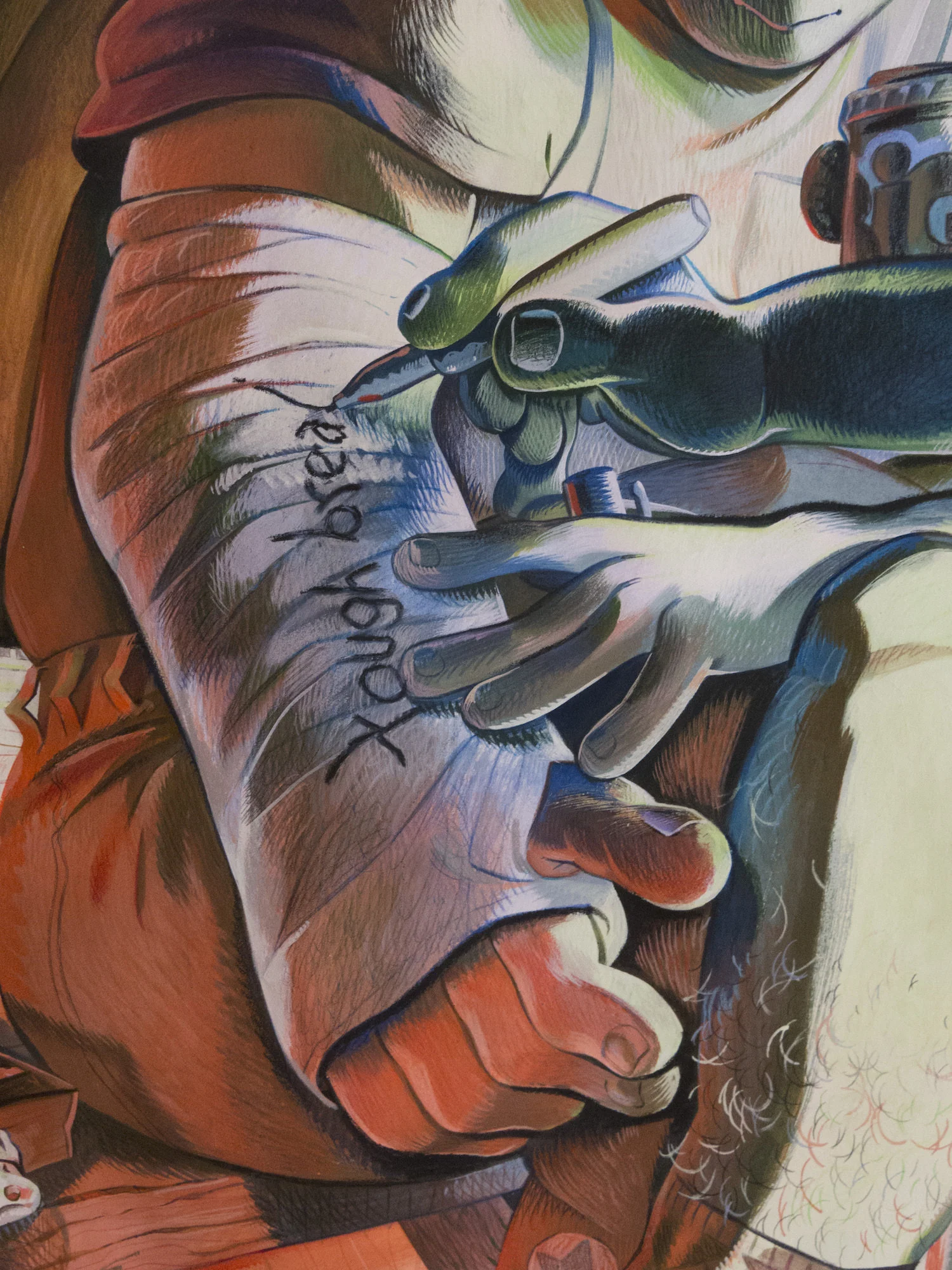

Over time, being in Holden’s presence and seeing art more regularly urged Jeremy to expand artistically - quite literally. “These paintings would not exist without Holden,” he says, gesturing towards four large pieces pinned along his bedroom wall. Rendered in gouache, oil pastel, and colored pencil, each 22” x 30” painting amplifies seemingly mundane moments - the stacking of plastic cups at a house party, the casual intimacy between a group of gossiping friends - into tableaus of theater. A few months ago, he cleared out a bright corner of his bedroom to work bigger; a space devoted just to painting. He didn’t think about prioritizing the space until meeting Holden.

“It sounds kind of cheesy, but it's only been within the past year that I've sort of made peace with calling myself an artist,” says Jeremy, 30. “I was so used to being told there is only one way to do this, and that it's through commercial art.”

Additional images provided by Jeremy Sorese and Holden Brown.

This shift occurred, in part, through collaborating on projects that have married their separate worlds: the conceptual precision of Holden’s installations, which utilize objects as proxies for suburban anxiety and the afterlife, with the candor of Jeremy’s cartoonistic depictions of mostly queer bodies, in all their fleshy candor. “What really excites me about collaborating with Jeremy is finding the ways in which cartooning and the fine art world can coexist to create something new,” says Holden. “Something that speaks to people on a broader level, that doesn't feel so exclusive in a way.”

Their first collaboration resulted in the ultimate mark of achievement: a gash across Holden’s left cheek. It happened last Halloween, at their installation for the Wassaic Project’s annual Haunted Mill, in upstate New York. Instead of zombies and vampires, they replicated a home invasion, the forcible entry into an occupied residence, which Jeremy had been exploring in his upcoming book. They called their installation “Night of the Hunter,” a nod to one of Holden’s favorite films, the 1955 thriller starring Robert Mitchum as a widow-stalking serial killer.

Visitors walked down a dim domestic hallway that narrowed to a window, through which an animated silhouette of a foreboding figure was projected, peering through the rain. Once the lights fully darkened, Holden emerged through a side door wielding a machete. In a fit of terror, one teenager kicked the door into his face.

“Well, we were successful at what we set out to do,” Holden remembers thinking after recoiling from the door’s impact, machete still in hand. Blood formed on his cheek. “Maybe too successful.”

Collaborating was also scary: “It’s like starting a new relationship within the relationship,” says Holden, who cops to being a bit “micromanage-y” when it comes to his work. He recalls one blow up they had over the wallpaper pattern lining the hallway, which Jeremy had spray painted upside down. Instead of saying anything, he stared at it, uncontrollably fixated. “It’s a haunted house - only I would've noticed,” says Holden. “But I’m used to creating work that is very rigid. There isn’t really room for expressionism, so the hard thing for me is relinquishing control and allowing Jeremy's aesthetic to seep in. The walls don't need to be straight, the window can be wonky and candlestick can be papier-mâché. It becomes less about the technical aspects and more about the overall feeling, the emotion, and giving into that was a difficult thing for me.”

In March, Holden directed the music video for “Trophy,” a song by the singer-songwriter Kate Davis. Jeremy storyboarded the video, which involved Kate donning various forms of drag and killing contestants in a Star Search-like talent competition. As Holden was busy directing, Jeremy noticed two pieces of carpet buckling, creating a barely perceptible seam. As if seeing the glitch through Holden’s eyes, he rushed over to staple gun down the flaps.

“Fixing it felt like understanding another part of him,” says Jeremy. “During the haunted mill, I wasn’t able to do that yet; I just didn't have enough Holden-isms in me yet.”

This artistic recognition - of their own weaknesses, of their partner’s needs - has unexpectedly brought them closer as a couple. “I feel like I have such a deeper understanding of Jeremy and the way he works now,” says Holden. “Through collaborating, we learned to be better at communicating and vocalizing our needs.” Though he’s also tended to date other artists, “I haven't really collaborated with other partners,” he says. “I was always afraid of giving away too much of myself. Dating Jeremy has made me realize that collaboration doesn't have to mean giving something up - that it actually enriches my creative life.”

23 May 2019

Words by:Mitchell Kuga

- Share