Selling Out: An Artist’s Search for Money and Meaning

- 11 October 2016

- ByHallie Bateman

- 6 min read

Hallie Bateman recently illustrated Julia Edelman's Love Voltaire Us Apart: A Philosopher’s Guide to Relationships, available now. You can see more of her work regularly in The New Yorker and Lenny Letter.

In 2010 I walked home from my college’s mailroom with a check in my hand. I’d sold my first piece of art. The check was for just $60, but it made the $40,000 college degree I was pursuing seem trivial and unappealing. I was far more excited by the possibility the check offered: that I could be an artist.

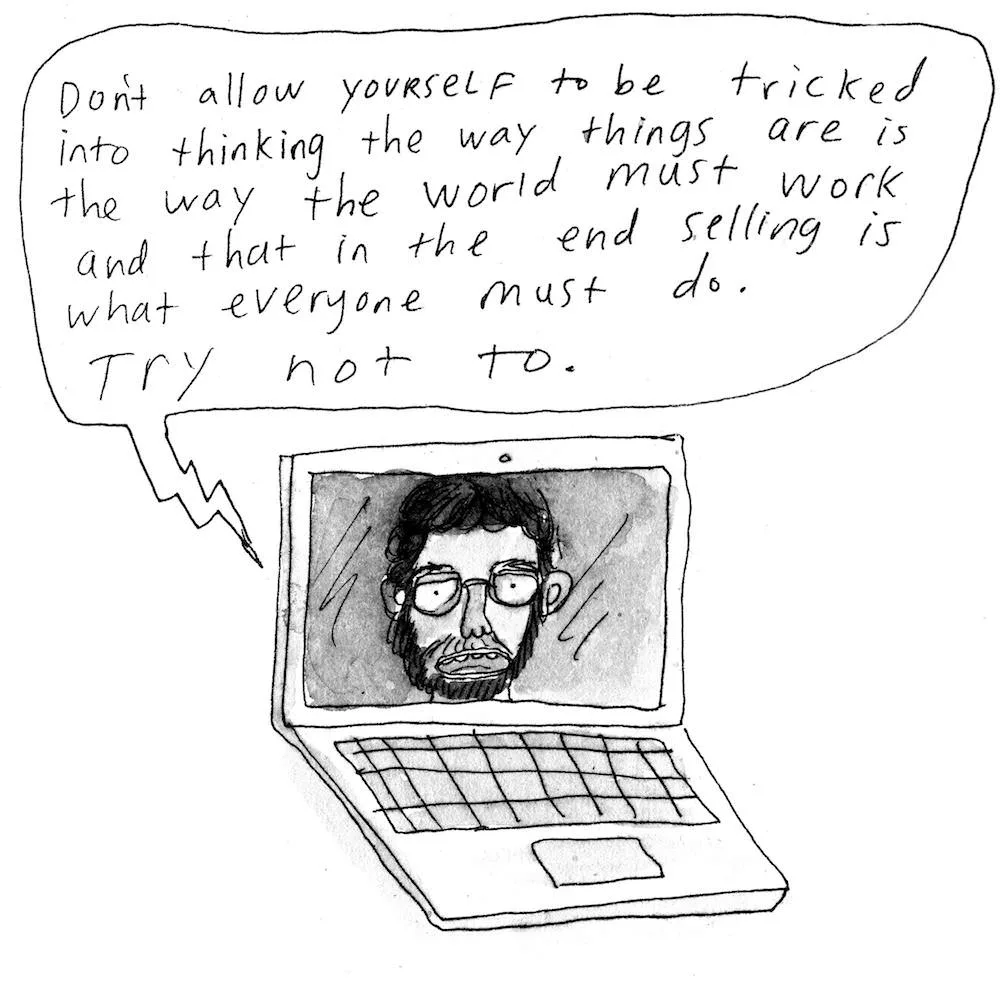

In the years to follow, I got encouragement from my mom, and sometimes from others. Eventually I got paychecks, too. I stayed up late nights, exploring life on the page, and listened again and again to a 2011 speech by one of my creative idols, screenwriter Charlie Kaufman:

If you say, ‘There aren’t words to put this moan I feel in me, but I’m going to swim in it and see what happens,’ you’ll end up with something real. But you’ll have to throw away any predetermined notion of what real is. It doesn’t mean you’ll end up with a million dollar screenplay or that critics will love it. You can write to that if that’s your goal. In the process you might lose track of who you are but that’s okay. They’ll assign you an identity.

This summer, I finished my first book. When the check from the publisher arrived, I ripped open the envelope, half expecting confetti. Instead I found a piece of paper with a number on it - not even enough to cover my rent. It wasn’t a surprise. After all, when I signed the contract I placed value on everything but money: The publisher was prestigious, I’d get experience in publishing, and it seemed like it would be fun. The check was exactly the amount I’d agreed to. So why was I so disappointed? The reasons I’d had for doing the book suddenly seemed vain and foolish. I needed to pay rent and buy groceries.

Just as that first check had convinced me I was an artist, this one convinced me I was also a business. A shitty one.

The past five years have been rough on Charlie Kaufman, too. When his 2015 Oscar-nominated movie failed at the box office, he told an interviewer that his artistic legacy is of little value to him: “I have to pay my mortgage… The truth is that I want the freedom not to have to worry about paychecks.” Silly me. Silly Charlie. We thought we could have one without the other. In this day and age, is it even possible to make noble art outside the harsh demands of commercialism? It’s tempting to imagine how things might be different:

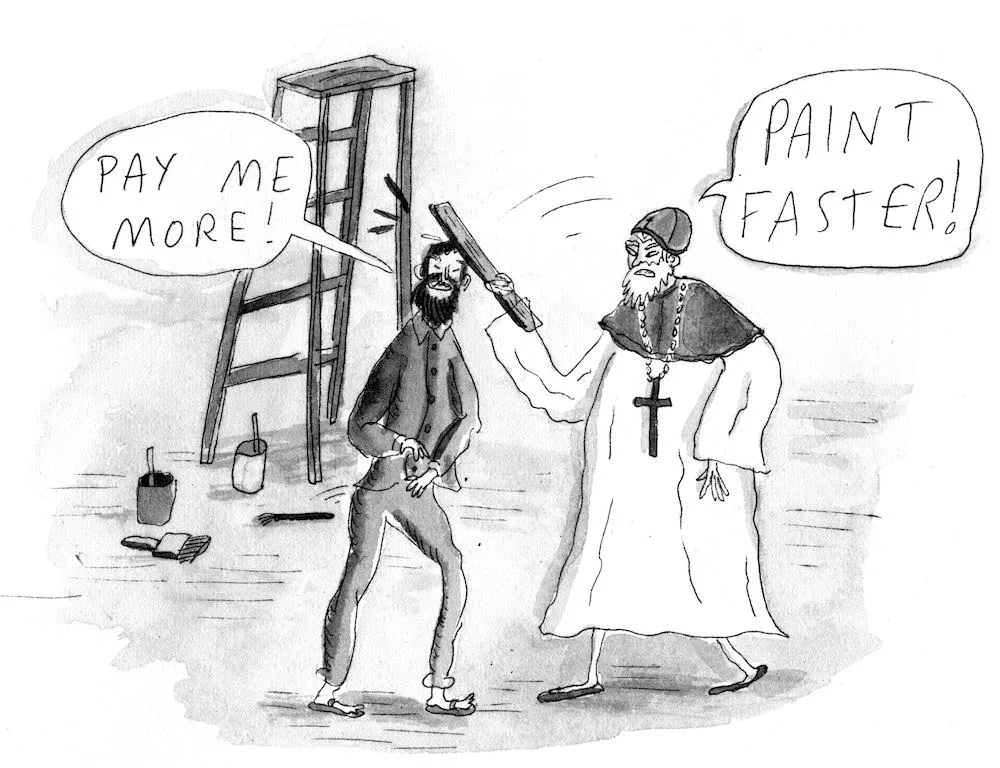

If only I had been born in olden times, I could make masterpieces in peace!*

(*This really happened. Pope Julius bopped Michelangelo on the head with a stick while he was working on the Sistine Chapel.)

If only I could be a fine artist, I could escape commercial art into a world where the artist is truly free!

If only I could hide away in a remote attic, far from worldly concerns!

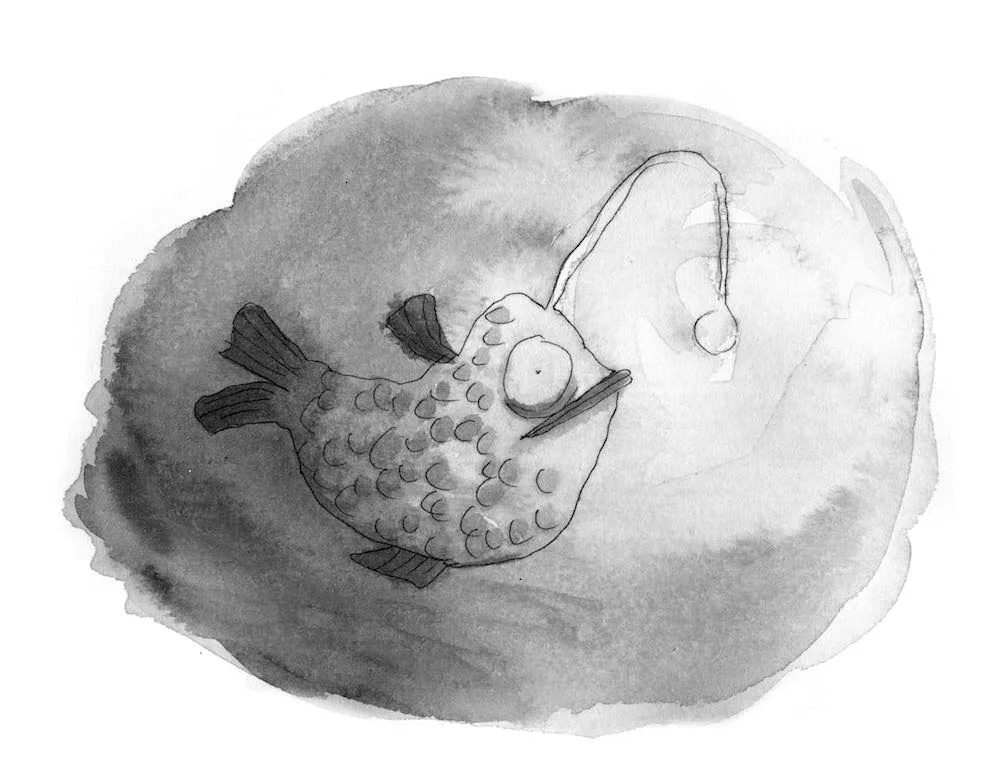

It’s tempting to think of the artist and the moneymaker as entirely different organisms with different environments, wants and needs. It’s tempting to put them in tidy compartments. I recently watched the “Deep Ocean” episode of Planet Earth, so we’ll use sea creatures for our metaphors here:

But ask any ocean scientist and they will confirm that the artfish and the bizfish don’t exist. Not just as literal organisms, but as effective metaphors. The artist and the businessperson are mysteriously, complicatedly bound together. After all, it wasn’t the businessperson in me that was excited by that $60 check in 2010, it was the artist. I was excited because the check was a sign that my communication had been received. I made something that was meaningful to me. Tentatively, I put it out into the world. The check was a ripple back from the universe, telling me, “This is meaningful to me, too! Please, do go on!”

Do not consult the oceanographer on this one (I just googled “ocean scientist”): I think the artist and the businessperson are wrapped up into one creature. Like a lantern fish. It dives deep, scouring the ocean floor for truth. And money. And then it sends ripples out into the ocean, relaying its findings to the other creatures. And asking for money.

(Is this whole fish metaphor a stretch? You try watching the “Deep Ocean” episode of Planet Earth and not drawing a lantern fish at every opportunity.)

Even after I draw enough fish to wrap my head around the fact that my job is to make decisions in the interest of money and art, I still constantly forget. Some days, I just want to send an email with the confidence and bluntness of graphic designer Mike Monteiro’s “F you, pay me.” Other days, I want to smash this computer, strip naked, and run through a field screaming painter James Ensor’s rallying cry, “Long live the peasant in art... long live free, free, free art!”

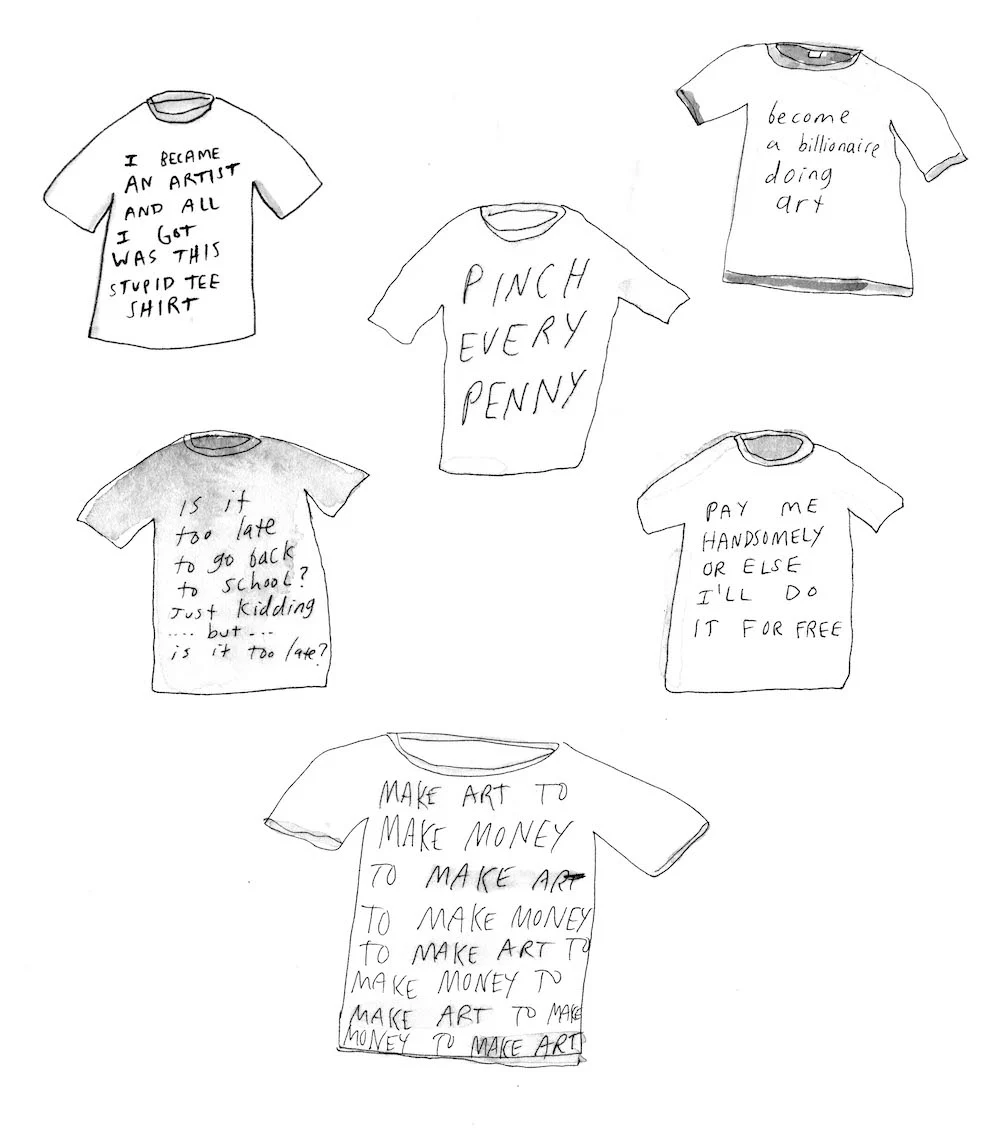

How can I remember? I think I need a catchy mantra. A snappy, T-shirt-ready slogan somewhere between these two on the spectrum, that messy place where most art is created.

Do any of these work? I don't know. I don't have time to figure it out. I have to go make art, because it’s my special gift I share with the world. And because I have to pay for the root canal I’m getting this week.

11 October 2016

Words by:Hallie Bateman

Tags

- Share